What is Immersive Storytelling (and Why Should You Do It)?

Immersive storytelling will unlock the true potential of your museum or attraction. But what is it precisely? And how can it increase visitor satisfaction and attract new audiences?

“Stepping forward, you feel a slight shiver of trepidation as your eyes struggle to penetrate the gloom. The first thing you sense is the noise – the distant howling of an Antarctic wind outside and, more loudly and worryingly, a series of ominous, sometimes downright alarming, creaks all round you.

You can feel the wooden planks of a ship’s deck under your feet and the smell of pitch fills your nose. As your eyes adjust, you realise the dim light is cast by oil lamps, gently flickering. Suddenly, the lamps sputter out and you’re pitched into utter darkness. Your breath quickens and your heart thuds loudly in your chest as, frantically, you wonder what will happen next.”

Those aren’t the first few lines of Patrick’s Cornwall’s latest naval blockbuster but the first few seconds of our Shackleton Immersive Cinema experience at the Fram Museum in Oslo. The experience of those first few moments demonstrates the power of immersive storytelling and highlights its two key aspects.

Firstly, this is all about placing your audience at the heart of the story. They’re there – in this case, stepping back 100 years into the gloomy hold of Shackleton’s Endurance as the life is slowly crushed out of it by the asphyxiating sea ice. They may be able to influence events, or they may be mere bystanders, but they’re going to experience the same events, the same emotions, as the people who were actually there.

Secondly, all of their senses are engaged. The distant howl of the Antarctic wind, the dim glow of the oil lamps, the feel of the wooden deck underfoot, the strong smell of pitch assailing their nostrils and snaking through their mouth on to their tongues.

So if that’s answered the question “what is immersion?”, what about the “why immersion?” query. Well, there are multiple reasons.

I’ve worked in marketing for over 20 years and the holy grail for marketers is word of mouth. That’s because people telling other people about your product or service is free. Of course, the theory’s the easy bit – in practice it’s much harder. But there are 2 key principals principles to generating word of mouth. The first is “unexpectedness“. The second is “emotion“.

It’s still the case that, the expectation of a museum experience involves lots of glass cases and lots of reading. Pitching people into the heart of an Antarctic ship as the sea ice squeezes it so hard it shoots out of the water, well, that’s unexpected – even in the most high profile of attractions.

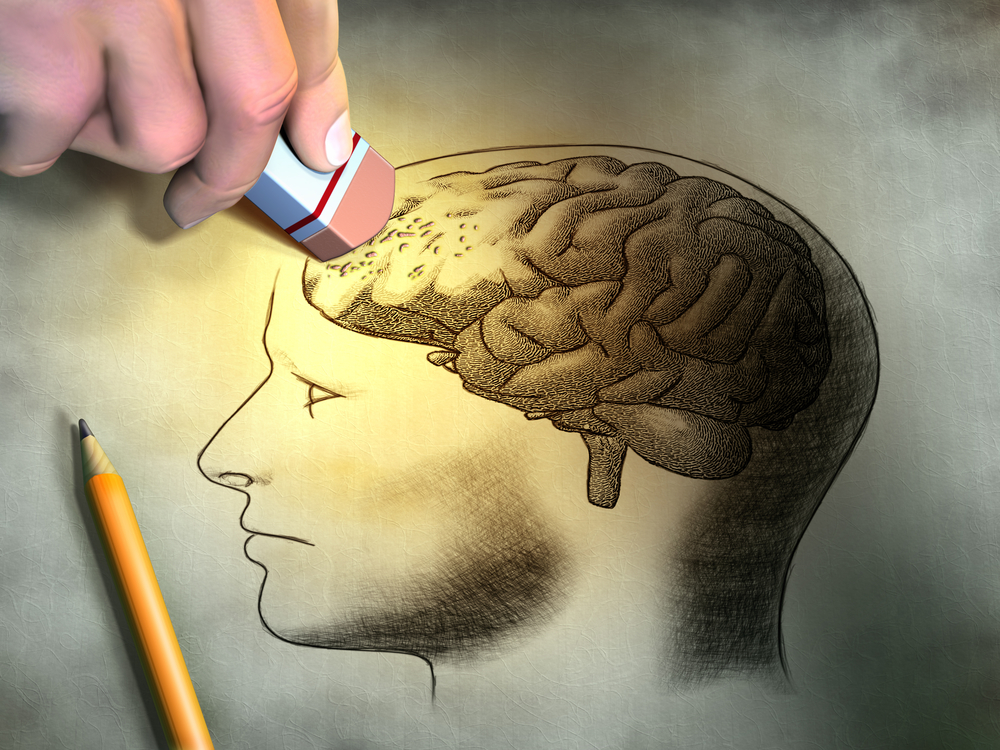

Words can stir the emotions no doubt but nothing can top the emotional impact of being there – of seeing what those involved would have seen, hearing what they would have heard, feeling what they would have felt. Each emotion stimulated creates a little hook in the memory – making it more likely they’ll recall your story long after any written account would have been forgotten. The sheer impact of stirring all those emotions will mean they’ll be desperate to share their experience with their friends and family.

So immersion can help your stories live longer with your visitors, and compel them to tell their friends. Not bad. But I also think it can do more. It can not only can it bring you new visitors but, it can bring in a different type of visitor.

Two groups are key to audience development – they’re Out and Abouters and Explorer Families (as defined by our friends at the National Trust – you can read more about their audience segments here.)

For these two groups, museums and heritage attractions are just one of a number of leisure time options. They have the desire to learn but it’s balanced with the desire to have fun – either with their partner or with their kids (or both). The traditional museum experience holds limited appeal but the chance to have fun while adding to their knowledge – well, that’s very attractive. Immersive storytelling ticks all their boxes

But there’s one final reason for this approach, and it has nothing to do with your visitors. When I was young, I used to run around castles and yearn to be a knight – to experience the pomp and chivalry of the joust, or the adrenalin-pumping adventure of battle. I’m sure you had similar childhood fantasies, otherwise you wouldn’t be doing what you do. With immersive storytelling, you can fulfill your own fantasies, and those of your visitors, even if they’ve been buried for decades. What could be more rewarding than that?

Immersive storytelling is groundbreaking, a little risky and may take you out of your comfort zone (although people like us are here to help.) But looking at your visitors ‘ wide-eyed stares of wonder and hearing their cries gasps of excitement makes all that effort worthwhile.

That’s why we do it, and why we think you should do it too.