Oculus Rift? HTC Vive? Google Cardboard? VR? AR? Confused? Read on to have the world of VR unravelled…

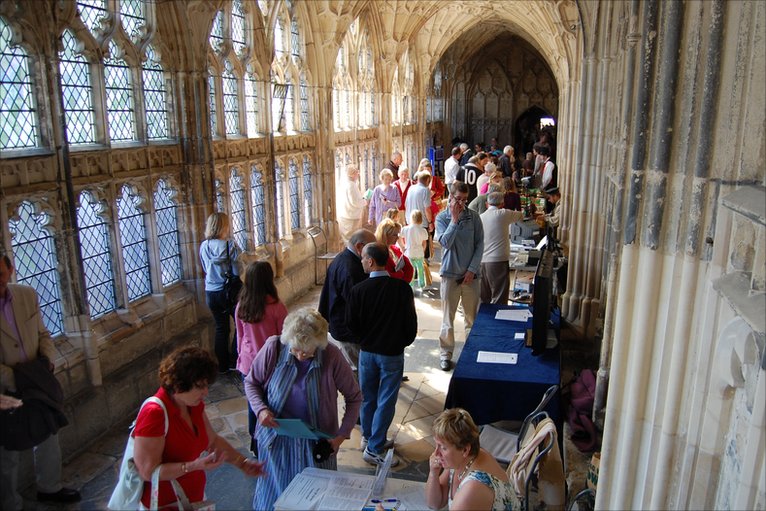

Oculus Rift VR.

By midday on Christmas Day, I’d already ridden a rollercoaster, flown unaided over a bottomless chasm and crept up close to a T-Rex tucking into his lunch.

If you’re making the assumption that I’d hit the mulled wine a little early, you’d be wrong. I’d been sampling the world of virtual reality, using the Google Cardboard I’d bought for my 2 boys (OK, yes, Dad was rather hogging their present.)

2016 is set to be a BIG year for virtual reality with headsets becoming commercially available for Facebook-owned Oculus, HTC-owned Hive and Sony-owned Playstation. And it’s already creating a buzz in our sector with British Museum and the Natural History Museum VR offering virtual reality experiences last year, and a Buckingham Palace VR experience launching on Google Expeditions just last week.

So what precisely is virtual reality? How are the proposed offerings going to differ? And how can you give it a whirl for yourself without getting your hands on one of the prized (and expensive) developers’ kits?

For a definition of virtual reality, I’m going to turn to a rather handy website I found dedicated to the subject (vrs.org.uk.) They defined VR as ‘a three dimensional, computer generated environment which can be explored and interacted with by a person.‘ It’s important to note that virtual reality takes you out of your environment and into a completely new world, not to be confused with augmented reality which digitally enhances your existing environment (that’s the subject for another post.)

The term virtual reality dates back to Jaron Lanier and the Visual Programming Lab in the 1980s (the 1992 film Lawnmower Man was based on Lanier) but certain aspects of virtual reality can be traced back to the 19th century and the first stereoscopic viewer developed by Charles Wheatstone in 1838.

All of the virtual reality offerings that I’m going to talk about are headset based – that is, you strap on a pair of goggles to enter your virtual reality world (vs. say a flight simulator, which is also a type of virtual reality but clearly isn’t headset based). From this base offering, the solutions differ in an attempt to create more realism. Some are purely visual , others bring your hands into the virtual reality world with you so you can manipulate objects, and others allow you to move around (that is, using your own feet rather than a games console controller).

All are striving for the holy grail of ‘sense of presence’, where the experience is so close to how you interact with the real world that you brain tells you you’re actually there. The opposite of this is ‘sense of nausea’ – created by the VR graphics rendering too slowly, creating a mismatch with the motion sensors in your ears and producing the VR equivalent of travel sickness.

OK – so I’m hoping you’ve got a sense of what VR is, and what makes it less virtual and more reality. Let’s take a brief look at the different offerings out there.

Oculus

Oculus was the company that propelled virtual reality back onto the agenda. Founder by a teenage Palmer Luckey, the instigator of a wildly successful Kickstarter campaign in 2012, the company has been Facebook-owned since 2014.

The Oculus Rift headset features 2 high resolution graphic displays (one for each eye, so you get the stereoscopic 3D effect), complete 360 degree head tracking, a 110 degree field of view and over ear headphones for a 3D audio effect. It also comes with a external sensor (to detect your movements), Oculus controller (for moving around and interacting with your VR environment) and an Xbox One controller (because many of the games developed for the Rift will require the controller for movement, shooting etc.)

The Rift is already available for pre-order ($599 if you’re thinking of buying one) and will be shipping at the end of March. The Touch sensors, which will enable users to point, wave, pick up virtual objects with their hands etc won’t be available until next quarter.

You should know that the Rift is a ‘wired’ experience (i.e. your headset will be wired to PC) and you’ll need a high specification PC (8GB of RAM, high specification graphics card) for it to work.

Oculus is the solution for those who want to create a top end VR experience for visitors to their museum or attraction and have a significant budget to invest in the hardware and the content. The Oculus Rift audience is going to be pretty niche initially – due to the investment required to get set up – so even if your experience is made available to download, there aren’t going to be that many people who’ll be doing it. That being said, because premium VR experiences will be rare, you’ll have visitors queueing up to try it out.

HTC Vive

Yes – you’re right, HTC are a primarily a mobile phone manufacturer. They rather took the tech industry by surprise when they announced the Vive at the Game Developers’ Conference last March. It may not have the first mover advantage of the Rift – pre-orders don’t start until 29th February with shipments starting in April – but in one way, the Vive promises to be an even more immersive experience than the Rift. Why? The ability to physically move around in the virtual world.

While the Rift is designed to be primarily a ‘sit down’ device, the Vive comes with laser trackers that allow you to move around in a small space – up to 15 foot by 15 foot, to be precise. As you’ve got a pair of goggles strapped to your face and can’t see the objects around you, it has a ‘chaparone’ mode which brings outlines of those obstacles into your virtual world so you don’t bump into anything.

Other than that, the Vive is very similar to the Rift – same resolution of display, same field of view and a pair of controllers that bring your hands into your virtual world. It will also be a ‘wired’ experience requiring a powerful (and expensive) PC to run effectively.

If you’re offering VR in your museum or attraction, Vive would be a good choice especially if your content works with the concept of visitors moving around a little. Of those that have reviewed Vive and Rift, most rate the former as more realistic experience. However, I suspect it’s audience may be even smaller than that of the Rift – it simply doesn’t have the buzz, awareness and marketing muscle of its Facebook-owned rival.

Sony Playstation VR

This headset will be designed to work with Sony’s Playstation 4. It’s very similar in specification to the Rift and the Vive – a slightly narrower field of view and some rather natty LED’s on the front that remind me of Tron (remember that movie?) The main difference is that many people will already have the hardware – a Playstation 4 – required to use the headset and even if they don’t, it will cost them a fraction of the cost to purchase one of the high spec PCs required to operate the Rift and Vive.

However, because a console isn’t as powerful as a PC, the VR experience isn’t likely to be as ‘premium’ but because it’s more accessible, and selling into an existing community of gamers, I’d expect the Playstation VR to be an early leader in the ‘serious VR’ sector.

If you create a VR experience for Playstation, it may be slightly less premium but the hardware to run it at your museum or attraction is probably going to cost you an awful lot less!

Samsung Gear VR

The final 2 offerings we’re going to talk about – Samsung Gear VR and Google Cardboard – trade off quality of experience for accessibility as they both turn smartphone into a virtual reality viewer.

The Samsung Gear VR is the more sophisticated of the two. For £90 you get the headset which you put your phone into (it’s important to note that it only works with an S5 Note or S6/S6 Edge/S6 Edge+ at present). The headset itself comes with a touchpad, so you can interact with your virtual world, and it’s own sensors (which you connect to your phone via micro USB) for more sophisticated head tracking than the phone’s own sensors can handle.

Because it uses your phone, it’s an experience completely free of wires, but of course it’s nowhere near as sophisticated as the Vive, Rift or Playstation – primarily because the phone screen can’t deliver the resolution of the purpose built rivals.

That being said, it’s much cheaper hardware wise for you to offer than the 3 premium offerings, and your experience could ‘stretch’ beyond your museum as Gear VR experiences are so easy for people to download (via the Play Store) and try for themselves at home.

Google Cardboard

You can’t get much more accessible than a lump of cardboard that you can buy on Amazon for £9.99 , construct yourself and then can slot your smartphone into to create a virtual reality viewer. This is what I bought for my kids for Christmas and if you’re curious about VR but don’t want to fork out nigh on £1,500 for a top end experience, this is a great way to try it out for yourself.

Bear in mind it’s not going to work with any mobile – your phone needs to have a gyroscope so it can track your head movements. You could also do with c2GB of RAM to handle the software. Once you’ve established your phone is compatible, download Google Cardboard from the Play store to get yourself started and then pick one of any number of Google Cardboard VR experiences also available to download.

You’re not going to get any ‘sense of presence’ with Google but it’s alot of fun and a great introduction to VR.

If you create a cardboard VR experience, the hardware will cost you next to nothing and you can upload your experience to the Play/App Store and have a ready audience willing to download it and try it out.

That’s plenty enough to digest on VR for now. In the next couple of posts Dinah and I will share our experiences with VR – me with cardboard and Samsung Gear and Dinah with Oculus – our thoughts on what makes effective VR experiences and some applications for the museums and heritage sector.